Triads (lesson)

Intervals, Chords, Triads and Harmonies: Part 4 - Triads

Contents |

Introduction

Hi all, if you have been following along so far, you now know about the degrees of the scale and intervals. We're now going to start putting this to work for us in part 3 of the series - triads.

First of all, what is a triad? Well, its the simplest type of chord, one consisting of 3 distinct notes. Another way to look at it is as 2 intervals stacked on top of each other, sharing the middle note of the three. Basic chords such as C, F, G, E etc all qualify as triads, because although you may be able to play them on all 6 strings in some cases, there are only 3 distinct notes, some of which may be repeated. As the simplest of chords, triads are probably among the first chords you learnt as a beginner. In fact, triads are very versatile, and you can go a long way with them. They come in four different flavours. The first two are very common, the last two you may not have heard of before.

Major Triad

The major triad is probably the most common chord type you will encounter. We all know major chords - C,F,G,E,D,A,etc - these are all triads. Using the techniques we learnt in the last lesson (which is here if you missed it), we describe triads using intervals counting from the base note. A major triad consists of:

Root note

Major third

Perfect 5th

Using that recipe and varying root notes, you can create any major triad in the diatonic scale system - 12 in total.

What was that ? What is the diatonic scale system? I threw that in just to check you were listening; Diatonic is a term that refers to the types of scales almost exclusively used in western music, that consist of a mixture of half tones and whole tones - exactly the type of scales we have been using until now, with our T and S formulae - T T S T T T S for major for instance. The opposite of a diatonic scale would be a chromatic scale which is constructed entirely of half tones.

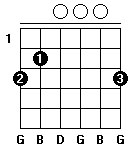

OK, back to major triads - lets try one out! In the key of G, the notes in the major scale are G,A,B,C,D,E,F#,G. Using our major triad formula, we pick out G,B and D - the notes in a G major triad. Check that against the G major chord you know - you should find that each note you play is one of those three.

You can finger the chord of G like this:

Minor Triad

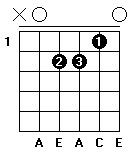

Ok, next up is the minor triad - just like your standard minor chords, like Am, or Dm. The minor triad differs from the major triad in that the first interval is a minor 3rd rather than a major 3rd - form our interval lesson we know that this means the 3rd note is flattened a semitone. Lets look at the triad of A minor. If we were trying for a major triad, we would look at the scale of A major - A, B, C#, D, E, F#, G#, A, and the major triad would be A, C#, E. But for the minor triad we would flatten the 3rd, to get A,C,E - which is consistent with the scale of A minor A,B,C,D,E,F,G,A. Notice that as we discussed in the previous lesson we can see that the minor scale is the same as the major scale with a flattened 3rd, 6th and 7th - the key of A shows this particularly clearly, as the notes we flatten to go from major to minor are all sharpened in the A major scale. We can remove the sharps (which is equivalent to moving the note down a semitone) to get the notes of the minor scale.

We could finger our Am triad like this:

Diminished Triad

The first two triad types, Major and Minor have changed the 3rd interval. The next two change the 5th interval instead of or as well as changing the 3rd. First the diminished chord. The rule for a diminished chord is that we use the root note, a minor 3rd, and a diminished 5th - no prizes for guessing why we call these diminished chords!

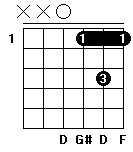

Our example for diminished chords will be Ddim. The scale of D is D,E,F#,G,A,B,C#,D. The root is D, the minor 3rd is an F, (one semitone down from F#), and our diminished 5th is Ab, or G#, again, one semitone down from our perfect 5th.

You could finger it like this:

In the guitar world at least, diminished triads are pretty uncommon - players prefer to use the diminished 7th chord which adds an extra note and makes the chord sound a little better. Its quite an odd sound, but very distinctive. Accomplished shredders very often will use diminished chords as the basis for arpeggios and sweeps to get a particular sound, very different from major or minors. They are often used to create tension which is resolved by a change to another chord, often the root.

Augmented Triad

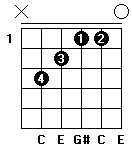

Finally, our last type is the Augmented triad. We get an augmented triad by using the root note, a major 3rd, and an augmented 5th. In this example we'll construct a C augmented triad. Using the scale of C - C,D,E,F,G,A,B,C, the root is C, the 3rd is E, and the augmented 5th would be a G# or Ab. You could finger it as below.

A very typical use for an augmented chord is as a bridge from the dominant to the tonic - remember those names from the lesson on degrees of the scale? We tend to use them occasionally when we are talking about chord functions. The tonic in the key of C is C itself, and the dominant is G. So what I said above translated to the key of C is that we can use an augmented chord to lead us from the dominant ( G ) back to the tonic ( C ). In this case, the chord sequence we would use would be:

G -> Gaug -> C

Why does this work so well? Its because of the way the individual notes move within the chords. The differing notes between a G and a Gaug is that 5th - it moves from a perfect 5th to an augmented 5th. In the chord of G that means moving from a D to a D#. The chord of C that we are resolving to happens to have an E note in it (it is the major 3rd), so we get a nice little sub-melody when we play those 3 chords - D, D#, E - which seems to lead us very pleasantly from the G chord to the C chord. This kind of movement within chord function accounts for a lot of the effects that different chord sequences have on the ear within the context of a particular song, and the cool thing is that in the first two lessons we covered the language and concepts to understand that kind of analysis - if nothing else, you can impress your fellow band members!

Other Triads

Now that we have covered the four types of triad you are probably wondering why there are only 4 types of triad - why can't we have a C triad with a minor 3rd with an augmented 5th for example? Well, there are no rules in music, all we are trying to do is explain something that at times can be pretty indefinable. The pragmatic answer to the question is that yes, of course you can do that. Its just that the results might not be too musical, and on the whole people avoid certain combinations of notes. However, it might well be the perfect chord to finish off your killer riff with, and if that is the case, be my guest and do it - in the next lesson we'll have a look at how we might go about naming some of the more esoteric chords like that, and you can figure its name out for yourself! (OK, since you asked, a C triad with a minor 3rd and an augmented 5th might be called Cm#5, but don't quote me on that!)

Final Words

Now that we have looked at the 4 types of triads, you have the ability to figure out the notes of any one of 48 different chords! That's 4 individual types for each of 12 keys. In the next lesson, we'll start to look at some more complex chords and pretty soon you'll be able to work out hundreds of chords just by memorizing a few simple rules!

As ever, feedback and questions are welcome.