Theory Basics for Guitar (lesson)

Hi all, and welcome to theory basics. This lesson introduces some of the basic concepts that we will be using in other lessons on the board. There are a lot of words and concepts that the beginner needs to pick up, this is an ideal place to start if you are a beginner, and will give you an insight into some of the language and concepts you need to move onto some of the more complex lessons.

Contents |

Note Naming and Octaves

Lets start off with how the the notes we all use are named. There are a total of 7 different notes in the scales that are commonly used in Western music. Some but not all notes are split into half notes (see tones and semi-tones later). We name the whole notes after letters of the alphabet, starting at A and moving through to G. At G we circle back around to A again. Once we have moved through 8 whole notes and got back to where we started from, the notes sound the same but higher. The notes with the same name are an Octave apart. Notes that are an octave apart are equivalent in musical function, they just sound higher or lower. In fact, if two notes are an octave apart, the higher note will have twice the frequency of the lower note. Its called an octave because there are 8 notes in total, including the equivalent notes at the beginning and end of the sequence. The doubling in frequency between notes an Octave apart points to something in our nervous system that finds this relationship sensible and pleasant to listen to, so we organise our musical scales around this concept.

Flats and Sharps, Tones and Semi-tones

I said that there 8 whole notes - it turns out that we also need half notes to play any possible tune. By convention in western music, we place half notes between all of the whole notes except for 2 specific pairs - E,F and B,C. Why do we do this? It all stems form the way that Major scales are constructed, which you can read about in later lessons, here. We construct scales from a mixture of half and whole notes depending on the scale, and use of 8 whole notes along with some half notes gives us the flexibility to do this. Remember that music notation has developed over many thousands of years, so doesn't necessarily make perfect sense, but it soon becomes second nature when you start working with it.

The half notes are called semi-tones, and the whole notes are called tones. We have 2 ways to refer to the semitones. We can figure them by raising a semi-tone from a particular note, which we call a sharp, and we use the '#' sign to denote this. Or, we can figure the note by stepping down a semitone from a higher note - we call this a flat, and use the 'b' to denote this. So, we can talk about the notes A and B, and the note in between them which we could call A# or Bb.

Remember above when I said that certain pairs of notes do not have a semitone between them? Another way of saying this is that there is no such note as E#, or B#, or using the flat notation, Fb and Cb do not exist.

(Side note : Actually there are some unusual circumstances in which we talk about E#, B#, Fb and Cb, but these are really notational devices, and don't refer to additional notes. We will learn about this later).

So you should now see that there are actually 12 distinct semi-tones in an octave (we usually say 13 because we count the octave note as well). These are: A, A#/Bb, B, C, C#/Db, D, D#/Eb, E, F, F#/Gb, G, G#/Ab and back to A again making 13. In Western music, no other notes than these exist, and every song written uses a combination of these in various octaves, so a tune or melody is simply a sequence of semi-tones A-G# spaced apart and with some notion of rythym so that they are not all equally spaced.

Why 12 Semitones? Why not more or less? The simple answer is convention. Western music settled on the 8 note scale a long time ago, and uses half notes as the fundamental basis for all music. Some cultures use quarter notes in their scales, but they sound strange to western ears. Occasionally on guitar we use quarter note bends to add emphasis and phrasing, especially in blues, but we do not construct scales out of them

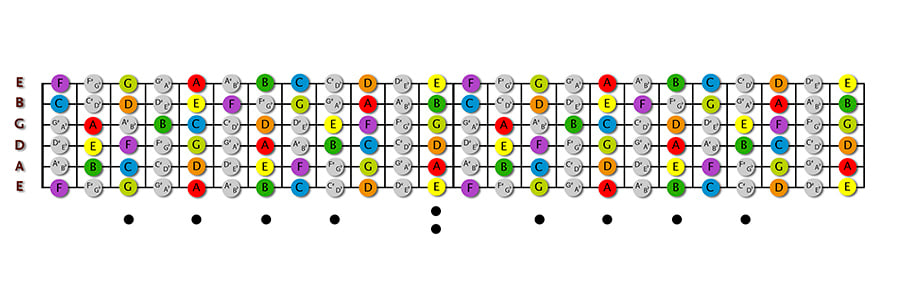

Notes on the Guitar

Next, it might be a good idea to learn where all of these notes are on a guitar. Fortunately, its easy to work out with some basic knowledge. Owing to the fact that there are 6 strings on the guitar, and they are all tuned differently, and the fact that the notes repeat when you get to an octave, there are many places you can play a given note on a guitar. It all starts with knowing the notes made by the open strings. An open string is what we call a string that is played without the left hand pressing on it anywhere to fret a note. By contrast a fretted note (we would often say something like "play the 3rd fret") is a note in which you left hand presses down on the string in between the frets, forcing the string to rest against a fret and play a higher note.

So, what are the open strings? Starting from the highest (and thinnest) string and moving upwards (upwards because you are looking down at the guitar), the notes are E, B, G, D, A, E - remember this! Another way of reffering to the strings is by number. The thin E string is called the first string, the B string is called the second string, and so on, to the 6th E string.

Now, how do we make the rest of the notes? Very simple, you just fret the string and play it.

How do we figure out what the notes are? The rule is simple. Moving up a fret means you move up a semitone. Lets play a G. How can we do that? The easiest way is to play the open G or 3rd string, but there are many other options, and you can play one or more G notes on each string. Lets take the first string. We know that open it is an E, so at the 1st fret it is an F (no E# remember?). The 2nd fret would be an F#. The 3rd fret would be ... G! That was easy, lets try another.

Starting on the B string - B, C (no B#), C#, D, D#, E, F (no E#), F#, G - so that is the 8th fret.

Just for completeness, here are all the notes on the fretboard:

That's all there is to it! Its worth while memorizing all of the notes on the fretboard, it wil help you later on.

Scales and Keys

Scales are the foundation of Western music - and a scale is nothing but an arrangement of notes! To make up a scale, we take a selection of notes from the list I gave you earlier and arrange them in ascending order. It is the spacing of the notes in a scale that gives it a character that is imposed on the song. Once we have a scale, we use it to select notes for the tune of the song, and use it to make chords out of, so as you can see, the idea of a scale underlies everything we do musically. A lot of songs will have one scale throughout but there is nothing stopping you from using as many scales as you want in a song.

Since there are so many possible combinations of all of the notes ahown above, we tend to organize scales into families, and use a formula for each family. For instance, the formula for a major scale is actually the spacings between the notes in the scale, and is discussed in the Major scale lesson here. Once you have a formula for a scale type, you can use it with any starting note to get 12 variations. Examples of scale families are Major, Minor, Minor Pentatonic - we might talk about a C major scale, a Bb Minor scale or an A minor pentatonic scale. There are literally hundreds of different scale types, but don't worry, I just mentioned the 3 most common, and its perfectly possible to be an acomplished musician if you only ever learn those 3 variations. However, scales are extremely important, and if you want to be a decent guitarist you need to put in the time to learn these and other scales and be able to play them quickly and cleanly without thinking about it.

A key is best understood initially as a scale family type along with the note you are starting the scale from. So keys could be A Major, B Minor etc. In fact, we usually only use the major and minor scale types to denote a key. A key is different from a scale in that it defines the tonal centre of a piece of music - that is to say the chord that the song keeps returning to. It is possble to use different scales and chords in passing in a piece, yet remain in the original key.

Chords

Chords are simply a number of notes played together at the same time. They are usually strummed on the guitar (strumming means taking your pick and playing all of the notes in the chord together with a simple downward or upward sweep, so the notes sound as near to simultaneously as possible). There are many different chord types- chords have their own rules for construction, using specific selections of notes from a scale. Again, like scales, chords have families, and the 2 most common are Major and Minor - so named because their notes are selected from Major and Minor scales respectively. Actually that is a slight simplification as we will see in later lessons, but it is enough to give you the idea for now.

That's it for today - hopefully that should have given you some basic concepts which we will build on in later lessons. If you have any questions I'll see you on the forum!

Thanks to Javari for supplying the awesome fretboard diagram!

Editorial note: published 2007-12-10