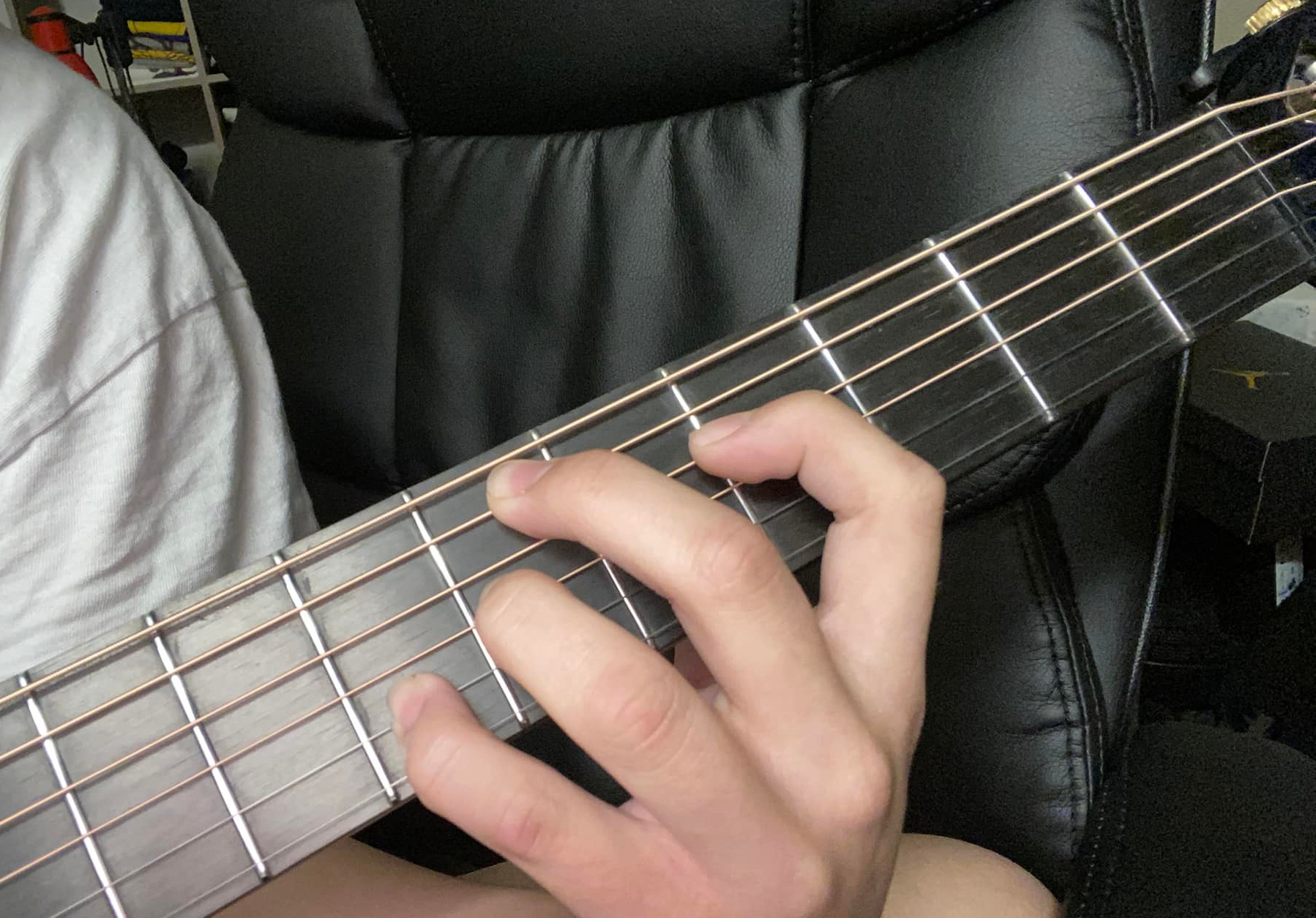

Someone asked about what this chord was on Facebook:

And there was a lot of people saying either "Hendrix chord" or "Ebm7#9", "Ebm#9" and similar. Other got it as Ebm7, which I think is most correct, disregarding any open strings - but they original post didn't mention those. But it prompted me to write a longer reply, and I wanted to share it with you guys, as it explains my thought process:

-----------------First reply from me-----------------

Your chord is an Ebm7. Not sure where people are getting this "#9" from. You have an Eb (root), Gb (minor 3rd), Db (7th). These are the notes. It's common practice to omit the 5th, as it doesn't hold any defining quality. Repeating a note, which is already in the chord, an octave above doesn't suddenly make it a Ebm7(#9). That #9 would be the same as the minor 3rd, and it's already stated that it's a minor chord, thus having a minor 3rd.

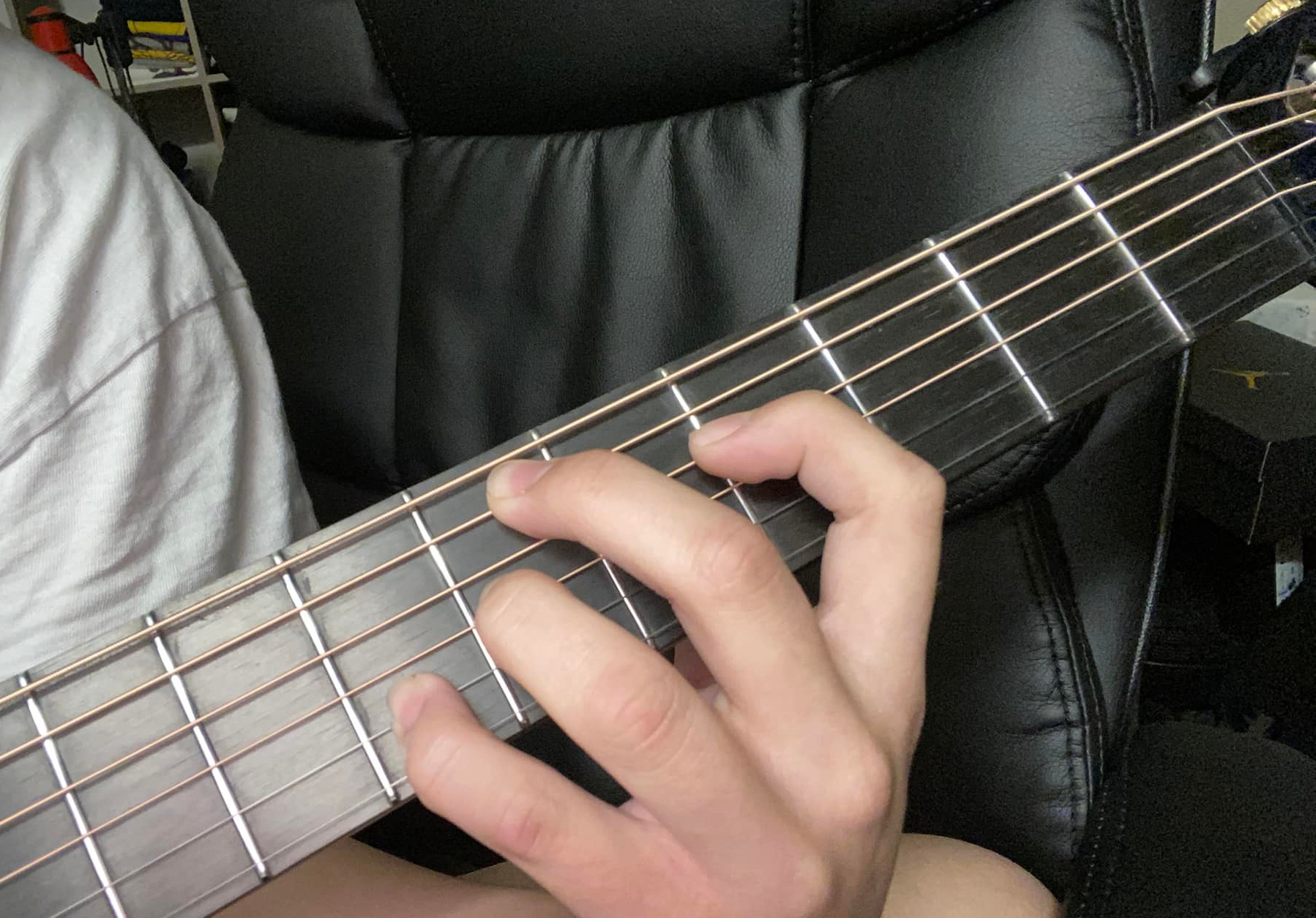

As an example:

You don't write an open Em7, i.e. 022033 chord as E(5)x7#9x13#17 or something silly. I've probably managed to confuse myself here, but it just proves the point as well as hurt my brain. It would just be an Em7.

022033 = EBEGDG = E G B D = Em7

And

not E(5)x7#9x13#17...

E(5)=E, B

x7 (double sharp 7) = E

#9 = G

x13 (double sharp 13) = D

#17 = G

-----------------First comment over-----------------

Someone else replied to me:

"Your point is valid. I suppose it is from familiarity with E7#9. It is a bit further down the path of understanding that a chord, by convention, cannot contain two different notes designated as a third. Without using the #9 designation we would have both a major third and a minor third in one chord. When the major third in E7#9 is flattened to a minor third there is no need for the added designation because the two notes are now both minor thirds an octave apart.

Word salad comes to mind as I too hurt my brain trying to add to this discourse."

-----------------Reply to the above-----------------

Yup, if you have a major third, then the #9 can be added.

The upper extensions can be confusing at first, but if you start to bring them down in the same octave as the triad underneath it starts to clear it up a bit, in my opinion. I.e. C7#9:

Triad: C E G

7th: Bb

#9: Eb

Had the triad been a Cm you would be looking at this, where it would not make sense to repeat the Eb as a "#9":

Triad: C Eb G

7th: Bb

(#9: Eb)

Even if you're not familiar with all the names for extensions, you can work this out on a piano by playing a simple triad, and as you add exentions it will not be necesary to add the extension name if the note is already present in the triad.

Of course talking about chord tones, non-chord tones, extensions and what kind of feel or tension they create becomes a bit more advanced as go from major chord and minor chord into dominant chords. The very simple explanation I suppose is that minor and major chords, even with their respective 7th added, are more "stable" and not "tense". The dominant chords are already tense in their interval relations, so adding say a b9 only builds more tension.

Staying strictly to root position of the chords, as inversions can create different "flavors" too:

Personally, to my ear, even up to a min11-chord sounds stable, where as a maj11 start to not do so due to that b5-interval now between 7th and 11th and the b9 between 3rd and 11th, ie. in Cmaj11 the 7th (cool.gif and 11th (F) creates the b5-interval and 3rd (E) and 11th(F) the b9-interval. You could even see it as a C major chord (C E G) with a Bdim chord (B D F) on top.

In min11 you still have some relatively pleasent intervals. I.e. Cm11: (C Eb G)+(Bb D F). Essentially a C minor chord with a Bb major chord on top.

----

Going to the 13th extensions is where it starts to get more confusing, or where I need more time to think - or my current knowledge breaks down.

**Gonna try to see if I can grasp some logic of the 13ths here**...don't take this as anything but me trying to make some sense and describing my thought process:

Essentially a 13th in a maj13, is the same as a major 6th interval, as in a Cmaj13: *C* (1) *E* (major 3rd) *G* (5th) *B* (major 7th) *D* (major 9th) *F* (perfect 11th, same as 4th) *A* (major 13th).

C major scale: *C* (1) *D* (major 2nd) *E* (major 3rd) *F* (perfect 4th) *G* (perfect 5th) *A* (major 6th) *B* (major 7th).

We must remember that "maj" belongs to "C" and not to "13". It is a Cmaj chord and thus the 13th (same as 6th) is naturally a major 6th/13th. From our root, C, to the 6th, we have 9 half steps here, making it a major 6th.

Sticking to the key of C major, we could construct a minor chord from A minor, the 6th degree in the scale:

A min: A C E

And you would think it would be:

Am13: A C E G B D F

But...

A minor scale: *A* (1) *B* (major 2nd) *C* (minor 3rd) *D* (perfect 4th) *E* (perfect 5th) *F* (minor 6th) *G* (minor 7th)

However, if we remember that the "min" (m) belongs to the triad (A minor) and doesn't describe the "min 13th" interval, as that would usually be described with "b13" (or b6 for 6th chords), it would be Am(b13). The b13th is the same as a b6th, which is 8 half steps.

This means calling the above an Am13 would be wrong, as that "13" only has 8 half steps, where as the "13" in Cmaj13 has 9 half steps. How do we differentiate between them? One is 13, the other is b13. Cmaj13 and Amin(6). However...

...then we're going into the land of b6's. If only dealing with a minor triad + the b6th, such as a Am(b6), it is more commonly seen as the first inversion of a maj7. A C E F vs. F A C E.

Talking about Am6, the "m" describes it being a minor chord and the

"6th" describes it having a major 6th. Otherwise it would be b6. Essentially the same goes for Amin13, which theoretically includes the 7th, 9th, 11th and 13th), however since it's not a b13, that Am13 chord would be: A C E G B D F#, which are the notes from the G major/E minor scale. And the min13 chord is only ever present from the 2nd degree of the major scale - also referred to as the dorian mode. In C major scale, as we started out with, the only min13 chord that has those intervals is the D minor, which relates to the dorian mode.

Comparing minor chords from the C major scale with all the natural extentions from just the C major scale:

D minor: root, minor 3rd, perfect 5th, minor 7th, major 9th, perfect 11th, major 13th. It's a *Dm13*.

E minor: root, minor 3rd, perfect 5th, minor 7th, minor 9th, perfect 11th, minor 13th. It's something like an Em7add11(b9)(b13) chord, but it's much easier to just say it's a G13 or G13/E if we want to indicate E in the bass. Same notes.

A minor: root, minor 3rd, perfect 5th, minor 7th, major 9th, perfect 11th, minor 13th. It's an Am(b13), but essentially easier to think of as a C13 or C13/A.

Dominant chords (R-3-5-b7) become a much bigger discussion, as they deal better/differently with tension added from non-chord tones and even non-scale tones. I.e.

G7#9#11: R-3-5-b7-#9-#11.

G7#9#11: G-B-D-F-A#-C#

That's for another day...

-----------------Comment over-----------------

I'm sure I've made mistakes along the way, but breaking it down further like the above helped me a bit.

You are at GuitarMasterClass.net

Don't miss today's

free lick. Plus all our lessons are packed with

free content!

This post has been edited by Caelumamittendum: Dec 15 2021, 07:54 PM

Caelumamittendum A Reply To A Facebook Post: Dec 15 2021, 07:04 PM

Caelumamittendum A Reply To A Facebook Post: Dec 15 2021, 07:04 PM

Phil66 I fully concur with Ben Dec 15 2021, 08:51 PM

Phil66 I fully concur with Ben Dec 15 2021, 08:51 PM

Caelumamittendum QUOTE (Phil66 @ Dec 15 2021, 09:51 PM) I ... Dec 15 2021, 10:40 PM

Caelumamittendum QUOTE (Phil66 @ Dec 15 2021, 09:51 PM) I ... Dec 15 2021, 10:40 PM

Phil66 QUOTE (Caelumamittendum @ Dec 15 2021, 09... Dec 15 2021, 10:55 PM

Phil66 QUOTE (Caelumamittendum @ Dec 15 2021, 09... Dec 15 2021, 10:55 PM

Caelumamittendum This one is a good short video with more clear com... Dec 15 2021, 11:27 PM

Caelumamittendum This one is a good short video with more clear com... Dec 15 2021, 11:27 PM

Todd Simpson I fully concur as well Very concise. Dec 16 2021, 07:21 AM

Todd Simpson I fully concur as well Very concise. Dec 16 2021, 07:21 AM

tflava Nice topic.

More stuff to think is that one chord ... Dec 16 2021, 08:54 AM

tflava Nice topic.

More stuff to think is that one chord ... Dec 16 2021, 08:54 AM

Caelumamittendum QUOTE (tflava @ Dec 16 2021, 09:54 AM) Ni... Dec 16 2021, 03:57 PM

Caelumamittendum QUOTE (tflava @ Dec 16 2021, 09:54 AM) Ni... Dec 16 2021, 03:57 PM

Phil66 QUOTE (Caelumamittendum @ Dec 16 2021, 02... Dec 16 2021, 07:54 PM

Phil66 QUOTE (Caelumamittendum @ Dec 16 2021, 02... Dec 16 2021, 07:54 PM

Phil66 I think I'll stick to my continuous second ord... Dec 16 2021, 10:04 AM

Phil66 I think I'll stick to my continuous second ord... Dec 16 2021, 10:04 AM

PosterBoy I looked at that and my eyes went to the part of t... Dec 16 2021, 11:24 AM

PosterBoy I looked at that and my eyes went to the part of t... Dec 16 2021, 11:24 AM

klasaine Yes and no (of course I get Collier's sentimen... Dec 16 2021, 06:41 PM

klasaine Yes and no (of course I get Collier's sentimen... Dec 16 2021, 06:41 PM

Caelumamittendum QUOTE (klasaine @ Dec 16 2021, 07:41 PM) ... Dec 16 2021, 07:34 PM

Caelumamittendum QUOTE (klasaine @ Dec 16 2021, 07:41 PM) ... Dec 16 2021, 07:34 PM

klasaine QUOTE (Caelumamittendum @ Dec 16 2021, 11... Dec 16 2021, 08:23 PM

klasaine QUOTE (Caelumamittendum @ Dec 16 2021, 11... Dec 16 2021, 08:23 PM

Caelumamittendum QUOTE (klasaine @ Dec 16 2021, 09:23 PM) ... Dec 16 2021, 08:30 PM

Caelumamittendum QUOTE (klasaine @ Dec 16 2021, 09:23 PM) ... Dec 16 2021, 08:30 PM